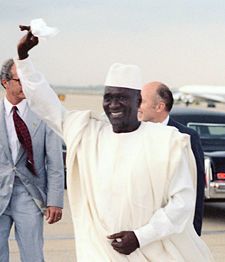

Ahmed Sékou Touré

| Ahmed Sékou Touré | |

| |

| | |

|---|---|

| In office October 2, 1958 – March 26, 1984 | |

| Preceded by | None (position first established) |

| Succeeded by | Louis Lansana Beavogui |

| | |

| Born | January 9, 1922 Faranah, Guinea |

| Died | March 26, 1984 (aged 62) Cleveland, Ohio, United States |

| Nationality | Guinean |

| Political party | Democratic Party of Guinea |

| Religion | Muslim |

Ahmed Sékou Touré (var. Ahmen Seku Ture) (January 9, 1922--March 26, 1984) was an African political leader and president of the Republic of Guinea from 1958 to his death in 1984. Touré was one of the primary Guinean nationalists involved in the liberation of the country from France.

Contents[hide] |

Early life

Touré was born on January 9, 1922 into a poor family in the west African country of Guinea, while a colonial possession of France. His date of birth has never been formally established; there remains a contention that he was born in 1918 at Faranah. He was a member of the Mandinka ethnic group[1] and was the great-grandson of the famous Samory Touré[2], who had resisted French rule until his capture.

Touré's early life was characterized by challenges of authority, including during his education. Touré was obliged to work to take care of himself. He began working for the Postal Services (PTT), and quickly became involved in Labor Union activity. During his youth and after becoming president, Touré studied the works of communist philosophers, especially those of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.

Politics

Touré's first work in a political group was in the Postal Workers Union (PTT). In 1945, he was one of the founders of their labour Union, becoming the general secretary of the postal workers' union in 1945. In 1952, he became the leader of the Guinean Democratic Party which was local section of the RDA (African Democratic Rally, French: Rassemblement Démocratique Africain) , a party agitating for the decolonization of Africa. In 1956 he organized the Union Générale des Travailleurs d'Afrique Noire, French West Africa's first general trade union, and was involved in an element of the French Communist Party and the French CGT union. He was a leader of the RDA, working closely with a future rival, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who later became the president of the Côte d'Ivoire. In 1956 he was elected Guinea's deputy to the French national assembly and mayor of Conakry, positions he used to launch pointed criticisms of the colonial regime

Touré is remembered as a charismatic figure and while his legacy as president is often distained in his home country, he remains an icon of liberation in the wider African community.[citation needed] Touré served for some time as a representative of African groups in France, where he worked to negotiate for the independence of France's African colonies.

In 1958 Touré's RDA section in Guinea pushed for a "No" in the French Union referendum sponsored by the French government, and was the only one of France's African colonies to vote for immediate independence rather than continued association with France. Guinea became the only French colony to leave the French Community. In the event the rest of Francophone Africa gained its independence only two years later in 1960, but the French were extremely vindictive against Guinea: withdrawing abruptly, taking files, destroying infrastructure, and breaking political and economic ties.

As President of Guinea

In his home country, Touré was a strong president[3]. Opposition to single party rule grew slowly, and by the late 1960s those who opposed his government faced fear of detention camps and secret police. His detractors often had two choices--say nothing or go abroad. From 1965 to 1975 he ended all his relations with France, the former colonial power. Touré argued that Africa had lost much during colonization, and that Africa ought to retaliate by cutting off ties to former colonial nations. Only in 1978, as Guinea's ties with the Soviet Union soured, President of France Valéry Giscard d'Estaing first visited Guinea as a sign of reconciliation.

Throughout his dispute with France, Guinea maintained good relations with several socialist countries. However, Touré's attitude toward France was not generally well received, and some African countries ended diplomatic relations with Guinea over the incident. Despite this, Touré's move won the support of many anti-colonialist and Pan-African groups and leaders.

Touré's primary ally in the region was President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Modibo Keita of Mali. After Nkrumah was overthrown in a 1966 coup, Touré offered him a refuge in Guinea and made him co-president. [4] As a leader of the Pan-Africanist movement, he consistently spoke out against colonial powers, and befriended leaders from the African diaspora such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, to whom he offered asylum (and who took the two leaders names, as Kwame Ture).[5] He, with Nkrumah, helped in the formation of the All-African Peoples Revolutionary Party, and aided forces fighting Portuguese colonialism in neighboring Guinea-Bissau (for which the Portuguese launched an attack upon Conakry in 1970).

Relations with the United States fluctuated during the course of Touré's reign. While Touré was unimpressed with the Eisenhower administration's approach to Africa, he came to consider President John F. Kennedy a friend and an ally. He even came to state that Kennedy was his "only true friend in the outside world". He was impressed by Kennedy's interest in African development and commitment to civil rights in the United States. Touré blamed Guinean labor unrest in 1962 on Soviet interference and turned to the United States.

Relations with Washington soured, however, after Kennedy's death. When a Guinean delegation was imprisoned in Ghana, after the overthrow of Nkrumah, Touré blamed Washington. He feared that the Central Intelligence Agency was plotting against his own regime. Over time, Touré's increasing paranoia led him to arrest large numbers of suspected political opponents and imprison them in camps, such as the notorious Camp Boiro National Guard Barracks. Tens of thousands of Guinean dissidents sought refuge in exile. [6] Once Guinea's reprochment with France began in the late 1970s, another section of his support, Marxists, began to oppose his government's increasing move to capitalist liberalisation. In 1978 he formally renounced Marxism and reestablished trade with the West. Running again for president unopposed, Touré was reelected in 1982.

Touré died in the city of Cleveland in the United States while undergoing heart surgery on March 26, 1984.

Dictator

Touré ruled as a dictator over Guinea from 1960 to 1984. During his presidency Touré led a strong policy based on Marxism, with the nationalization of foreign companies and strong planned economics. In 1960 Touré declared Guinea to be a one-party state, with GDP as the only party. Most of the opposition to his socialistic regime was arrested and jailed or exiled. His early actions to reject the French and then to appropriate wealth and farmland from traditional landlords [7] angered many powerful forces, but the increasing failure of his government to provide either economic opportunities or democratic rights angered more. While still revered in much of Africa[8] and in the Pan-African movement, many Guineans, and activists of the Left and Right in Europe, have become critical of Touré's failure to institute meaningful democracy or free media.[9].

To date, 50,000 people are believed to have been killed under the regime of Touré, many of them in the concentration camps Camp Boiro and Camp Camayenne, which operated from 1960 to 1984[10][11][12][13][14].

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please, leave a comment...